- Home

- Anjanette Delgado

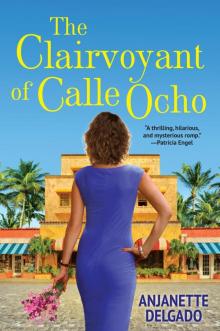

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho Page 2

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho Read online

Page 2

I wish I could say it was being the other woman that got me into all the trouble that followed. But it wasn’t. What really got me into trouble was being a lousy clairvoyant.

It started with the bad marriages. They were my first overt signs of blindness.

This is what happened: at twenty-four, and then at thirty-five, I married two apparently different men who turned out to be exactly the same. Both cheated on me, and both must have studied from the same user’s manual (as in manual for using others), because when I divorced them, both fought me for alimony and half of all I owned despite the fact that they were the ones who left me for other women. Why didn’t I know they were cheaters? Wouldn’t even a bad clairvoyant have had a clue at some point?

Well, that depends. It’s true that understanding men has nothing to do with predicting the future and everything to do with being able to see clearly what is already right in front of you. In other words, if you listen to what he’s actually saying, you’ll never have to wonder what he’s “really trying to tell” you. You’ll know what’s going to happen between you because very often what’s going to happen is the direct result of what is happening now. (Best clairvoyance lesson I ever learned.)

But here’s the thing: Psychics use feelings to see. What this means is that when our emotions are involved, our sight goes to hell. And how can your emotions not be involved when what is happening, is happening to you? Which explains how we can see your future, while being blinder than a severely myopic bat about our own screwed-up lives.

But I didn’t know any of this back then. In fact, not knowing this little tidbit was exactly what had made me renounce clairvoyance after my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer during my senior year of high school. I thought, What kind of a clairvoyant am I? How could I not have known? To the eighteen-year-old me, I’d as good as killed my mother, or at least failed to save her, and was no better than an incompetent security guard asleep on the job and drooling on that guest sign-in pad. If my psychic power had seen it sooner, she might have lived. But it didn’t, and in my great guilt, and shame, I decided right then and there to kill my so-called gift by ignoring it forever.

And do you know what happens to a woman who goes through life refusing to see beyond the tip of her nose? She loses her “trouble radar” when it comes to men, that’s what. How else could I have been so dense as to marry the wrong man twice, and then decide that the only way to protect myself from loss was to become the other woman. To stick to married men. Wonderful, short-term men with no long-term expectations swirling about them. Men incapable of causing me further loss of free and clear Miami real estate or of my own estate of real being. Men I’d have to be crazy to grow attached to.

Or so I thought.

Because it was just this fearful, over-self-protective thinking that resulted in the very thing I was trying to avoid: I fell in love with one of them.

His name was Jorge, and he was, oh, so wrong. A free spirit, childlike, light, and impulsive, despite being in his mid-thirties then and only three years younger than I. He missed the family he’d left behind in Cuba and worked as a chef, while saving to bring the wife he’d married during a visit to his homeland. He was fun and kind and foolish, and very, very sexy. And he knew food. It was his religion and his native language, and he knew how to use it to fill you up until you cried with relief, or until what ailed you became loose, or until you loved him and became crazy with fear, with knowing that he could just as easily use this language of his to conquer your heart, as to demolish it.

So what did I do? I ran. Straight into the arms of the first “less dangerous” married man I found, which happened to be my married tenant of several years, Hector.

Yep, it must have been the fear of heartbreak that made me stupid, convincing me that I could get away with using Hector to protect myself from my own heart, that I could have an affair with him, right under the nose of his wife, Olivia. It was also this thinking that made me unable to see the terrible thing that would happen after he broke up with me, when it was too late for anything, really.

That’s when I had one of my dreams, the first in years. It was a strange dream and in it, all I knew was that something very bad was about to happen and that I was somehow responsible. It was just a dream, so I ignored it. I mean, when was the last time my instincts had pointed me in the right direction?

Unfortunately for me, for the first time in years, this time they turned out to be absolutely right.

Chapter 3

Yes, it was good for me too, thank you very much. Sex with Hector at the Hotel St. Michel always was.

But.

For the first time in eight months, the moment it was over, he went into the bathroom to wash instead of lounging in bed talking about a million silly things with me. Which is probably the only reason his earlier comment came back to haunt me, loud as an ambulance siren, as I lay in bed covered only with a sheet: “We are different people with different lives.” And then there was the line in the book. What was that about?

Despite the fabulous foreplay, “somesing” was not right. How did I know? Because the one infallible thing men have taught me is that if a man is in a big rush to get to another area of his life right after sex—for whatever reason, no matter how reasonable, and even if only mentally—something’s wrong, and you don’t need to be clairvoyant to know it. No exceptions.

“Everything all right?” I asked when he came out of the bathroom.

“Yes. Sure. Why?”

“Yes-sure-why—because you seem anxious and rushed. That’s yes-sure-why.”

“I’m not rushed.”

But he didn’t step out onto the suite’s narrow balcony in his boxers to smoke his cigar or try to scare me into thinking he’d pee right onto some unsuspecting doorman standing solicitously by the St. Michel’s entrance.

“Should we order coffee? Maybe one of those little lava chocolate soufflés you like so much?” I asked.

“Sorry. I can’t. I have this bookstore thing, this meeting. It’s very important. You stay and rest if you want to.”

I looked at the digital clock on the nightstand.

“A meeting at almost five in the afternoon?”

“Yes.”

“On a Wednesday?”

“Yes, on a Wednesday, and, Mariela, please. Whatever you do, don’t do that, okay?”

I knew what he meant: Don’t break the sacred mistress oath and start acting like a wife.

“You’re right. I’m being silly,” I said, jumping up and grabbing the underwear, T-shirt, and jeans I’d worn to the hotel and heading to the bathroom. “I have things to do too. Landlord things. In fact, you should give me a ride back to the building.”

“Now?”

“Yes, now,” I said, mimicking his tone. “What’s wrong? You not headed down there?”

He sighed, looking more than a little displeased. “Yes, of course. Go take a shower then, so we can leave.”

“I need to deal with a few things,” I said, as if I had to justify myself.

He was silent. Didn’t even give me an absentminded nod. Something was definitely up. This was the opposite of the detail-oriented, experience-motivated Hector I knew prided himself on “taking care” of a woman “before, during, and after.”

“I can always just get a cab,” I called out before closing the bathroom door.

“No, no. I’ll just, eh, drop you off a few blocks away,” he said, doing his usual pause when using American colloquialisms. They fascinated him, always making him think about their literal meaning.

“Nothing we haven’t done before, right?” I said.

In fact, we’d done it plenty of times in the eight months since our affair began because, as I might have told you before, Hector, and his wife, happened to be my tenants.

I own a small fourplex building the size and shape of a big house, with two floors, and two apartments per floor. I lived in apartamento uno, while Hector and Olivia had lived in apartamento cuatro for alm

ost three years now. I didn’t plan such an inconvenient arrangement, but you can see why it wouldn’t have done to carry on anywhere near his home or mine, which were as close to the same thing as they could be without being exactly so.

My other tenants were Gustavo and Ellie. Gustavo’s apartamento dos was located directly across from mine on the first floor, both our homes having the entryway on one side and the stairway to the second floor on the other. He was a single guy in his early thirties who worked at a neighborhood hardware store by day and sculpted kinetic metal works of art by night.

Upstairs in apartamento tres, directly above mine, and across from Hector and Olivia’s apartamento cuatro, was Ellie, who was in her mid-twenties, worked as a cashier at the McDonald’s on Calle Ocho and Fifteenth Avenue, and had begun to make a habit of not paying rent until the month was close to over and I’d threatened her with eviction.

“All right, flaca, just hurry up, please,” he said, resigned, heading for the balcony, cigar in hand. “You know, you should really buy a car. It doesn’t have to be new. Just something to get around.”

“You know I’m scared of driving, and don’t say, ‘Get over it.’ I’ve already tried.”

“I know, but this is Miami. Who lives in Miami without a car?”

“I do,” I said. (Where was this coming from? Hector knew I worked from home and did most of my errands and shopping online.) “And why do I suddenly need a car, exactly?”

He looked at me as if the exact reason were entirely obvious, then said, “You should think about a car,” and stepped out onto the balcony.

I got into the shower wondering what was suddenly so wrong.

As I lathered up, a distantly familiar fog began to envelop me so subtly that, at first, I thought it was just all that steaming hot water this side of the closed bathroom door. Then the fog spoke. Somewhere inside of me, it said, “This is the beginning of the end.” And that was all it said. But before you go saying, “Well, duh,” let me tell you that this is exactly how we all deceive ourselves when trying to figure out our love affairs. In fact, I said the same thing to myself that afternoon. I thought, What’s so special about thinking that it’s ending with my lover, when he’s so suddenly, and for the first time in our history, in a rush to leave my side after sex?

Having ignored my instincts for so long, I’d lost the ability to appreciate the difference between my own conscious mind and a message given to me with a certainty and force that I could physically feel. The fog had not said, “Maybe he’s getting tired of you. Maybe it’s over,” as my own insecurity would’ve said, and did. It read, “This is the beginning of the end.” I say “read” because the effect was one of seeing words in a foreign language that slowly became clear and understandable when translated.

I should’ve listened, but it had been a very long time since I’d been clairvoyant. I was sure my inner sight was dead, buried alive, or lost somewhere inside me, and never even considered the possibility that my gift might be making a half-assed appearance in a last-ditch effort to save me from myself before it was too late. This is why, instead of paying attention to the unusual strength of that “doom and gloom” mist spraying its troubled essence over me, I chose to “use my head.” I told myself that his behavior was just reminding me of all those other unhappy endings. Then I rationalized: Maybe he was worried. Maybe something was wrong with his bookstore. Maybe he was just having an off day. All I needed to do was stop worrying, and if I should be right and this was the “beginning of over,” so be it. Hector was my lover, not the love of my life, I reminded myself.

Fifteen minutes later, we were in his restored to perfection, black 1993 Saab 900 Turbo, silently heading toward Little Havana.

“Have I done something wrong?”

“No,” he answered in a tone I’d never heard him use before.

I stared at him until he sighed, turned on NPR’s All Things Considered, and without taking his eyes off the road, put his right hand on my knee before saying, “Look, sorry about being such a boludo. How you say in English? The one with the j?”

“Jerk?”

“Yes, but, no, eh—”

“Jackass.”

“That one. Look, I’m sorry, eh? I just have a lot of estress. You understand, right? It’s okay?” he asked, smiling at me now.

“Of course. Of course, it’s okay,” I said, pulling his earlobe playfully and noticing, with a sinking feeling, how relieved I felt the instant he chose to speak to me as if nothing were wrong. So relieved as to believe that maybe nothing was, and going so far as to marvel over my own ability to “estress” myself out over absolutely nothing.

Chapter 4

So now I’m going to have to tell you about the list.

I believe every woman (except virgins and, maybe, nuns) has a list, be it written out on actual paper or on the multicolored Post-its of her memory.

No, not the list of every quality she wants in a man (which only works if you work on being all the things on the list first, by the way). The list I’m talking about is the one with the names of every man she’s ever slept with. Or every man she ever slept with whom she really loved. Or every man she ever slept with who was truly fabulous in bed, or whatever else is important for her to keep track of about the men she’s slept with.

And no matter what that is, or whether your list is made up of men or women for that matter, the parameters you’ve chosen to impose on that list of who you’ve let inside you, and what has happened afterward, say more about your past, present, and future than any tarot card reading ever will.

Mine listed every man I’d ever slept with who had given me a long-lasting reason to wish I hadn’t.

But, to be fair, you do choose them, these men, for a reason, and my reasons could always be traced back to my mother.

And since there’s no easy way to, say, slip in this bit of information, I’m just going to say it: My mother was a prostitute.

A smart, terribly beautiful, devastatingly voluptuous one. And unlike the dollar-store sluts who sometimes pollute the stoop of my Coffee Park fourplex walking around like hens without heads, she had a business strategy, a niche she liked to call “womanly kindness.” She knew there was a good possibility that a powerful man willing to pay for it was a man whose self-esteem was on vacation. She also knew that such a man craved a belly laugh when he made a joke and an admiring glance when he dropped his pants, more than he craved the bursting, raging, cataclysmic orgasms he was, purportedly, risking his marriage and reputation for. The reason my mother knew, or thought she knew, so much about men with power is that they were the only kind she’d “date”—powerful (and possibly corrupt) power brokers, bankers, and politicians, that was the rule. Good thing it was the late seventies and there were plenty of those to go around in Miami.

“Be nice to your men when you grow up, Mariela,” she’d say while braiding my hair on lazy Sunday afternoons. “Pick ’em up when they’re feeling down and they’ll never be able to forget you.”

But forget me they did, which goes to show that one woman’s fortune-making niche can be another’s losing streak.

And if my mother’s illness was the reason I was never much of a butterfly as a young woman, her lifestyle was the reason I grew up yearning for love, for a community, for a simple life, the opposite of what she’d had.

After she died, I sold our house and filled my hours with renting and managing the properties she had left me: a mid-century bungalow in the southeastern neighborhood of Pinecrest, a Mediterranean cottage in central Coral Gables, and the Coffee Park fourplex. I also worked part time at Lion Video, a small, artsy store specializing in foreign and hard-to-find films, and spent all my free time and money watching movies at the mall, missing her terribly and trying to go on with life all by myself.

Then I met my first husband, Alejandro.

He was forty-one years old to my twenty-five when we married. An avid reader who taught children with special needs, he had absolutely no money and was

as different from my mother’s “boyfriends” as I could possibly find.

At first, we were happy, probably because I didn’t know any better. I was young and welcomed his guidance and his stable routines. I liked being the wife and playing house and dreaming of the children we’d have. Six years later, I’d grown up and begun to enjoy him less, to feel stifled by his stability and bored by the sameness and the arbitrary nature of our, or rather his, routines.

It didn’t help that he seemed to save all his patience for his students. He was from Spain, where it’s considered slightly vulgar, but not uncommon, to tell people to go take it in the ass as a slang way of sending someone to hell. “A tomar por el saco, tío” he’d say in the middle of the slightest altercation. Incidentally, I had discovered that it was also the only way he liked to have sex, and I was seriously rethinking our marriage when he surprised me by leaving me for a local TV weather girl. Said he wanted a woman with a real career, not someone who “played” at being a real estate investor but spent all her time at the movies, talking to her tenants and neighbors, or on her computer.

Since, thanks to my mother’s real estate investments, I had a “level of solvency” that he had become “accustomed” to and a lifestyle his teacher’s salary could not maintain, and since he had no assets besides his Kia, while I had three very desirable, free and clear properties in then home-value-rich Miami, the judge gave him the Pinecrest seventies-style bungalow we lived in based on the value acquired by the property while we’d been married.

Oh, how I loved that house, so surrounded by trees in the middle of a neighborhood full of sixties-inspired slanted roofs. I could have fought for it, but by the time Alejandro and his lawyer were done with me, my will to speak, much less negotiate anything, had died, and my only hope was that he’d take it easy on the weather girl, she who had to stand to do her job.

I moved back to Coffee Park, my refuge after every failure, until a few years later, in a society-induced panic over turning thirty-five and not having children, I married Manuel and moved into the Coral Gables house with him.

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho