- Home

- Anjanette Delgado

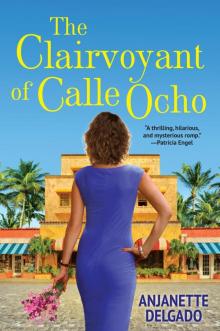

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho Page 3

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho Read online

Page 3

Manuel was the opposite of Alejandro. Puerto Rican, sexy, good in bed, really funny, and really irresponsible. Two years later, I had begun to tire of lying to people about his whereabouts when they called threatening to sue us if he didn’t finish the roof they’d already paid him to fix, when he managed to meet a yoga teacher who felt that supporting him was the least she could do in exchange for the “sheer joy” he brought into her life.

“You know what your problem is, Mariela? You don’t really see people. And you know why? ’Cause you’re just not spiritual. You don’t see people for who they can be. Do you even appreciate all I’ve done for you?” he’d said to me one of the many times I’d had to call to tell him that a very angry client was on my doorstep and that I’d give him his mistress’s address if he didn’t come and take care of it right away.

I remember taking some time after he said that to me to sift through my memories of our marriage, trying hard to think of what part of him I’d neglected to see, and though plenty of things came up, none were positive, so I guessed he was right. There must have been some good—there always is—and if I hadn’t seen it, it’s because I hadn’t been looking. He never truly saw me either, but I didn’t blame him for that. I’d never told him, or Alejandro, or anyone, about my mother, or about my stillborn clairvoyance. So how could I expect him to see what I hadn’t been willing to show?

This was almost three years ago and it had taken all this time to get the divorce finalized. In the end, I agreed to have him keep the Coral Gables house in exchange for a release of liability from his lawsuit-prone construction business on which I’d been an enthusiastic cosigner, stupid woman that I was.

It was a beautiful house in a great location right smack in the middle of Coral Gables, which is right smack in the middle of Miami. It had a big yard, a coral rock-rimmed pool, an all-around wooden fence, and rested on the quiet, tree-laden side of Aragon Avenue. Perhaps best of all, it was walking distance from Books and Books, an old-style independent bookstore and café that is, to this day, my very favorite place in all of Miami, not just for the books, but for the place itself, all wooden bookcases, Spanish-style iron railings, and a cozy courtyard with orange patio umbrellas and dangling garden lights on breezy autumn nights.

But I couldn’t afford the upkeep, there was no way to turn the house into a multifamily home, and at the time, the rent I could have gotten for it would barely have covered the taxes and landscaping. So I let him have it. Something told me that when the “joy” he’d be able to provide his new wife after paying Coral Gables’s obscenely high property taxes got too sheer for her taste, she’d promptly throw him out on his lazy ass.

I read somewhere that actress Zsa Zsa Gabor once said, “I am a marvelous housekeeper. Every time I leave a man I keep his house.” Well, you can think of Dumb and Dumber as the Zsa Zsa Gabors of my life and list.

After those two, I thought the problem might be marriage, the absurd need to complicate everything with the blatantly false promise (since the person making the promise cannot be absolutely sure he’ll be able to keep it) of security and exclusivity.

No longer did I wonder if my mother wouldn’t have been happier with an honest man willing to devote his life to her, instead of hurrying to live, and work, and save for her sunny horizon only to die from Olympic-speed cancer instead. No, my mother had had it right all along. It was my strategy of “normal” relationships based on “true love” that was wrong. And it wasn’t just marriage. It was the hope of “ever after” and the attachment that surely followed that had caused my poverty of both finances and faith.

I realized something had to change, so I changed it.

First, I moved back into my fourplex’s apartamento uno, hung a vintage, Chinese-red tin sign proclaiming me “The Landlord” on the door, and a hand-painted, cursive one on the window that read GESTIONES Y DILIGENCIAS, offering my services for odd jobs of a clerical nature. I knew a thing or two about lawyers, courts, and divorce, and how to find information using a computer. I could fill out forms and use a phone, and I was bilingual. So I bought a desk, a computer, a printer, and a fax and “opened” for business.

Second, I had to figure out a way to protect myself from my marrying heart. I couldn’t allow love to once again deliver me into the hands of a man who’d take what I had left and leave me asking what about me made me so easy to leave for another. Since all I had was real estate, it seemed to me that as long as I didn’t make the mistake of marrying, I was safe. Which is why, with the ink on divorce decree number two still wet, I made the very conscious decision to sleep with married men and only married men.

And who should come along but lucky number three.

I met Jorge through my tenant in apartamento dos, Gustavo, who brought him over one day and asked me if I’d help his friend with a small business loan application. Jorge wanted to make sure it was correctly filled out and didn’t trust his English as a second language skills. He also wanted to hire me to find a place where he could practice what he did know on the cheap, as he was saving to open a small café of his own.

He told me he’d been a chef and worked at some of the best Varadero hotels in Cuba before making his way out to sea, officially becoming a balsero (a rafter) and spending almost two years at the Guantánamo Bay prison camp for refugees during the 1994 exodus, before coming to Miami.

He was six feet tall, all bony muscle and energetic, fast-moving limbs. He walked fast, and it was a while before I noticed he slumped a bit from the habit of bending over the counter to be almost eye level with whatever he was cutting, chopping, or seeding. Instead, what I noticed the first time I saw him, was the wavy brown hair that looked good even though it seemed to go every which way, and his eyes, big and dark, giving him an air of mournful thoughtfulness. Until he smiled. Then they brought out his true nature: friendly and flirty, earnest, like a shy boy who has learned how to be daring, and I hadn’t been able to resist him.

He’d taught me how to dance salsa casino, how to cook, and how to tell a good joke using my body and all of my face. He also taught me how to play dominoes like an expert and the correct way to kiss the sides of fingers and ankles, the inner wrists, and the backs of the knees. (Open your mouth a little, push your lips out, and then softly drag the warm, fleshy, moist part of your lips over the chosen body part until your lower and upper lips meet on the skin. Stay there for a second. Breathe into the skin. Now kiss.)

How could he do all this with me while being married? Ay, my friend, I should tell you, if you don’t already know it, that when it comes to Cuba and Cubans, it’s always complicated.

After being in Miami for a while, he’d been allowed to go back to visit his mother. During the visit, he met Yuleidys, a nurse. They’d married sometime after that, but she couldn’t leave and he couldn’t go back there to live. After almost two years of visits and paperwork, she got her release papers from the Cuban government just before I met him, and for months had been supposed to arrive “any day now.” Theirs, I thought, was the most romantic relationship, made perfect by the ninety miles of sea between them, romanticized with letters, pictures, home videos, and long $1.29 per minute phone calls even in the post-Skype era of free international calling.

He had a kind heart and often stayed the entire night if he was off from the restaurant. He’d bring me café con leche in bed and always treated me as if what we had was real, as if he loved me, even though I knew I was just his temporary medicine against the loneliness and frustration with the politics of politics.

Not that I was his only remedy. He often dealt with his nostalgia by partying with his chef friends after he got off work, drinking wine and smoking pot until the wee hours of the morning, sleeping ’til all hours, and living his “promised land” life during the few hours before he had to be back for his shift.

“You’re so talented.... I don’t know why you treat your life like a light version of a Miami Vice episode,” I told him once.

It was a variation

of something I’d say more and more frequently over the six months we were together. He’d always answer the same thing:

“Mi vicio eres tú,” which meant that I was his vice, and sounded just as corny in Spanish as it does in English. But he’d say it in the softest voice while looking at me with the look you give the people you know you could never say no to.

One day, after a bowl of heavenly seafood soup, too much homemade tinto de verano (Place the following ingredients into a big glass jug: two cups of cheap Spanish rioja wine, one quarter cup of grenadine, a squirt of fresh lime juice, half a cup of fresh orange juice, half a cup of club soda, and four heaping tablespoons of brown sugar. Chill. Serve with a sprig of mint.) and sex, I made a mistake. I told him my secret: that I used to have to cover my ears to avoid the whispering and the calling of people I couldn’t always see, that I’d known what it was like to feel the dark weight of strangers’ secrets when they walked past me, and how I’d murdered it all the same way he’d be able to someday murder his nostalgia for the friends, the streets, and the little rituals of poverty he thought he’d left behind. I told him this to give him faith that his sadness too would pass. To give him something to hang on to. To keep him from partying his life away.

The next day, he begged me to go with him to see his godmother. She was Dominican but had fallen in love with a Cuban man and had lived in Cuba until the day he died. Now she lived in the Miami neighborhood of Allapattah, in a little blue frame house that was almost completely obscured by shrubs and fruit trees, and I had only to lay eyes on her to be scared out of my freckles.

She had brown skin and freaky green eyes, so intense they seemed fluorescent. But what scared me was her voice. The moment she spoke, it’s as if her voice’s shadow went off on its own to tell stories of women who threw themselves at the coffins of men they’d loved, of the trembling palms of young men about to pull triggers while looking into the eyes of other boys, and of the hearts of mothers, lurching and shaking in the knowledge that their daughters would not be coming home that night, or any night. It was a bit like a double sound track. One song is saying hello and asking Jorge how he knows me, and the other is performing a spoken poem made up of the world’s saddest headlines.

I think I scared her too, because two minutes after first taking my hands in hers, she opened her eyes wide as if urgently displeased with whatever I had “brought in with me.” Then both her voices became one, and this section of the poem was composed of the events of my entire life. She told me I could’ve had children but that it was too late now, and that I’d be tragically unhappy until I started respecting Yemayá’s will for my life, and started to see again like I was supposed to. Then she told her godson to stay away from me if he knew what was good for him because I’d have nothing to give him but problems, and proceeded to pretty much shoo and push us out of her house.

“Mariela, pero no le hagas caso a la vieja, por tu vida, tatica,” he said over and over again on the drive home, one hand on the wheel, the other holding my hands to his face, asking me to please forgive the crazy old woman, and to forgive him for bringing me, and even stopping the car on the side of the road to hug me until I’d stopped trembling, promising it would be a long time before he’d go see the dratted witch (bruja de mierda esa) again, even if she was his godmother. He’d only wanted to help. To show me I had nothing to be ashamed of. He’d wanted his godmother to figure out the perfectly logical reason I hadn’t seen my mother’s illness so I could understand it. But the experience had shaken me up so much that I continued to cry all the way home, and when a week later, he got notice of his wife’s release date two months hence, I convinced him it was a good idea to start preparing for his new life with fidelity and made him promise not to call me again, no matter what. I also promised myself I’d forget him and never again make the mistake of telling anyone about my truncated gift.

But my clairvoyance was not the only reason I ran away from him. I also did it because there’d been something there. Maybe not enough of a something to survive his crazy lifestyle, his even crazier godmother, and my own crazy habit of being drawn only to those relationships most bereft of possibility, but still . . . something. And that something made me want him to have a chance at what I thought I’d never have: a happy marriage, a real life.

I don’t say this now because time has passed. I knew what I felt then but figured his godmother was probably right about my having nothing for him. So I renounced him and worked on quickly filling the space he’d left empty before he came back for me, ignoring what I’d said about never contacting me because he realized he loved me so much (my secret fantasy) or I realized he’d never intended to.

Chapter 5

“You’ll be okay walking?” Hector asked, slowing down when we neared the corner of Twentieth Avenue and Eighth Street that afternoon. Fifteen minutes ago, we’d left the St. Michel, and already his mind was many worlds away.

“ ’Course. Not even dark yet.”

“Okay, flaca. Ciao then,” he said, forgetting to ask me to text him when I was within the safe confines of my apartment.

As I opened the car door, I hesitated, waiting for him to say that he’d call me later to wish me a good night, as usual. But he didn’t, so I got out, slowly walking away, my mind caught up in wondering what on earth could be preoccupying him to make him so abruptly distant.

I remember thinking that Hector was acting like a man about to embark on that wonderful time in the life of most affairs called “the beginning.” Only, I felt more like the wife than the mistress because if Hector was beginning something, it was certainly not with me.

I heard him drive away in the opposite direction and picked up my pace along the portion of Eighth Street that leads toward the Coffee Park section where I live, remembering to turn my head and cross the street when I passed the corner of Fifteenth, the street where Jorge lived, or maybe, used to live. I did this every time, even though I’d never once run into him in the year or so since we stopped seeing each other.

From that corner, it was a ten-to-fifteen-minute walk to my apartment and, since this is where all the madness was about to unfold, I might as well give you a quick history tour of the area: Little Havana, Coffee Park, and the civil war of sorts that made it a less than ordinary place to live in.

In the late 1990s, there was a movement to more broadly promote Little Havana as a tourist destination, the premier enclave of Cuban culture in the United States and site of the world’s largest outdoor Hispanic festival, Calle Ocho’s Carnaval Miami.

But tensions mounted when some of the more liberal residents began to feel that the nostalgic earthiness of Little Havana that had brought them there in the first place was being threatened by the city’s push to “clean up” and rebrand the area as a sanitized, commercialized, tourist-attracting destination.

“Look, Mariela, if I wanted to live in the suburbs of Disney World, I’d live in the fucking suburbs of Disney World,” Iris, who owned the fourplex next to mine, said to me at the time.

The result was that many of the “rebels” ended up moving to our side of Little Havana: Coffee Park, then really just a large square block of greenery and mature trees, but now surrounded by little coffee shops, independent “boutiques,” apartments that doubled as yoga studios, art co-ops, and holistic pharmacies attended by young bearded guys high on medicinal marijuana. Coffee Park became the symbol of neighborhood defiance, collectively and consciously turning up its nose at the bureaucrats, deciding that it was going to be as bohemian, progressive, and liberal as it got.

Of course, even as the little businesses sprouted all around, you still had the big Spanish-style houses turned rental duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes, most dating from the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, proudly holding their ground, alongside the storefronts. This made for a pretty self-contained community, whose people answered “Coffee Park” when asked where they lived, even though Coffee Park was, officially, and for most practical purposes, part of Little Havana.<

br />

My own fourplex was built in 1935, a big Spanish-style square of a building blessed with high ceilings, ornate moldings and arches, and big windows. Manuel, my second husband, had painted it a deep papaya color that I’d hated at the time, but had grown to love for the contrast of its orange-red hues against the green leaves and brown bark of the trees on the square across the street, all somehow fitting right in with the vintage awnings of the boho-chic storefronts.

Inside, it was a charming Spanish-style building with one-bedroom apartments, original hardwood floors, a nonworking fireplace in every unit, and fire escapes off each second-floor kitchen doubling as urban jungle gardens. There was also a small backyard taken over by a big avocado tree, its huge, shady limbs presiding over always-moist green grass.

But charming as my little building was, it was also a money drain. It needed the big roof and plumbing repairs that buildings require every fifteen to twenty years, and I often asked myself why I didn’t just sell the damn thing, knowing as soon as the idea crossed my mind that I simply couldn’t. It was all I had left from my mother, and, despite the real estate bubble’s recent noisy burst, it was the safest investment in the world. I mean, the area just had to take off, surrounded as it was by chic metro neighborhoods like Brickell, Downtown Miami, the Design District, and Wynwood.

I could see it becoming the next Greenwich Village before Greenwich Village realized it was cool, just as my mom had predicted. She bought the little fourplex at precisely the right time, in the middle of a housing slump and a few months before all the feuding about redeveloping Little Havana started. Back then, the square was just an improbable patch of green, located at the easternmost end of Calle Ocho and ridiculously close to Interstate 95. Still, she’d been determined to buy it, as if she’d somehow known that one day businesses, artists, and activists would begin moving into the houses and apartment buildings surrounding the park, turning the square into their own little bohemian enclave.

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho

The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho